Bonnie and Clyde tells a beautifully stylized modern-day, acrid fairy tale. A smash with the counterculture audience, the movie takes no shame with its gritty and glorified portrayal of violence, cynicysm, and sex. Released in 1967, during the height of the sexual revolution and campus unrest, “New Hollywood” had been born.

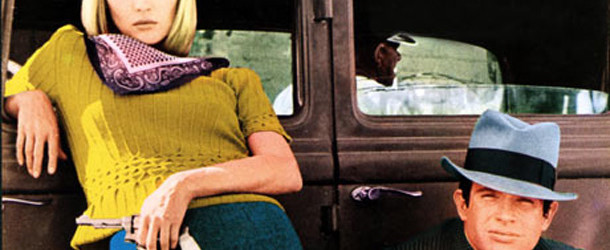

The story opens on Bonnie Parker, a young but bored blonde beauty. She hears a noise from her window and sees a handsome young man. This young man is Clyde. Unlike most fairy tale princes, he’s not there to woo her. He’s there to steal her car. But rather than be terrified of this, she finds it fascinating. Almost errotic. The two spark up a conversation and mark their first robbery together at a store in Bonnie’s hometown.

Along the way, they meet up with Clyde’s brother Bud, and his screeching wife Beverly.

Watching the movie, if you also watch a lot of ’60s movies, it definitely has a different style than the ones that came before. It’s editing is quicker and a bit choppy–almost French. There is a larger element of violence that had yet to be explored in American film. And sex is everywhere. From Clyde’s impotence to Bonnie using her sexuality as a form of manipulation.

This film is a landmark in that it sparked with the counterculture of the late 1960s. The phraise goes, “Life imitates art,” but here, art imitates life. Bonnie and Clyde reflect the attitudes of a new generation of moviegoers.

The two stars of the film are, well, the two brightest. Faye Dunaway plays Bonnie Parker in a starmaking turn. I don’t usually like Dunaway, but she’s great here. This is her best role. She peaked early. Estelle Parsons is the only member of the cast to win for her performance. Probably because she is the loudest and the comic relief.

Largely, the film is a basterdized account of history. It leaves out a lot of murders, jail sentences, and characters that really occured with these two in the 1930s, and the events that led up to their famous deaths are misconstrued. As far as telling a story goes, though, those omissions don’t matter, provided that viewers don’t take this movie as a documentary.